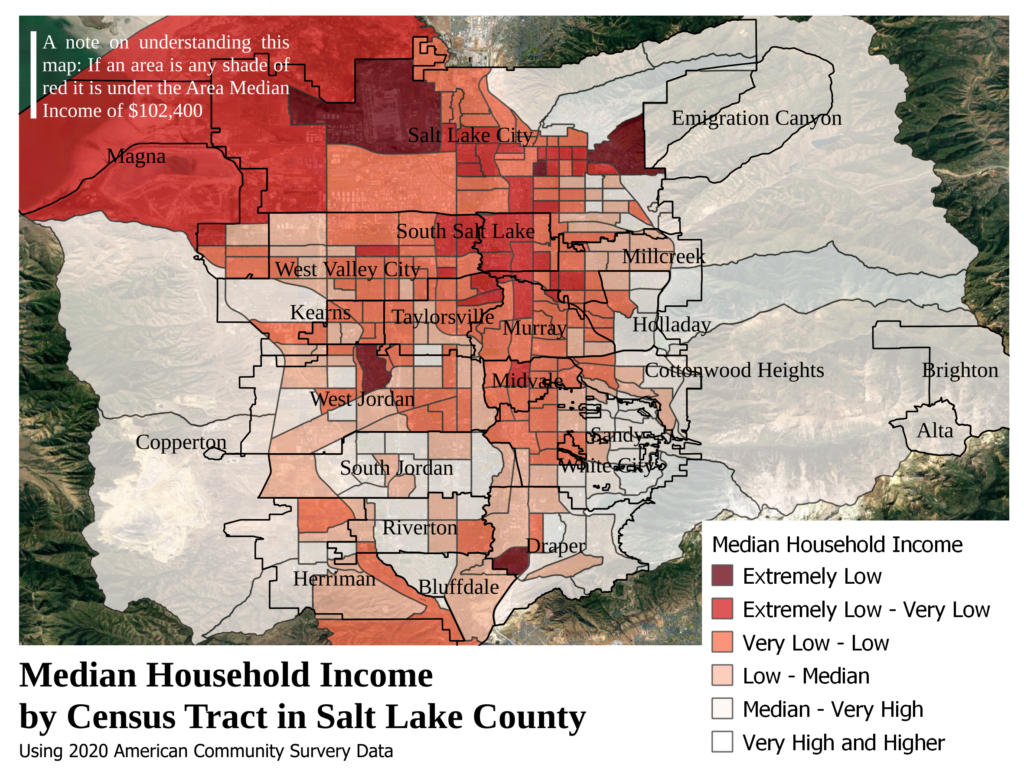

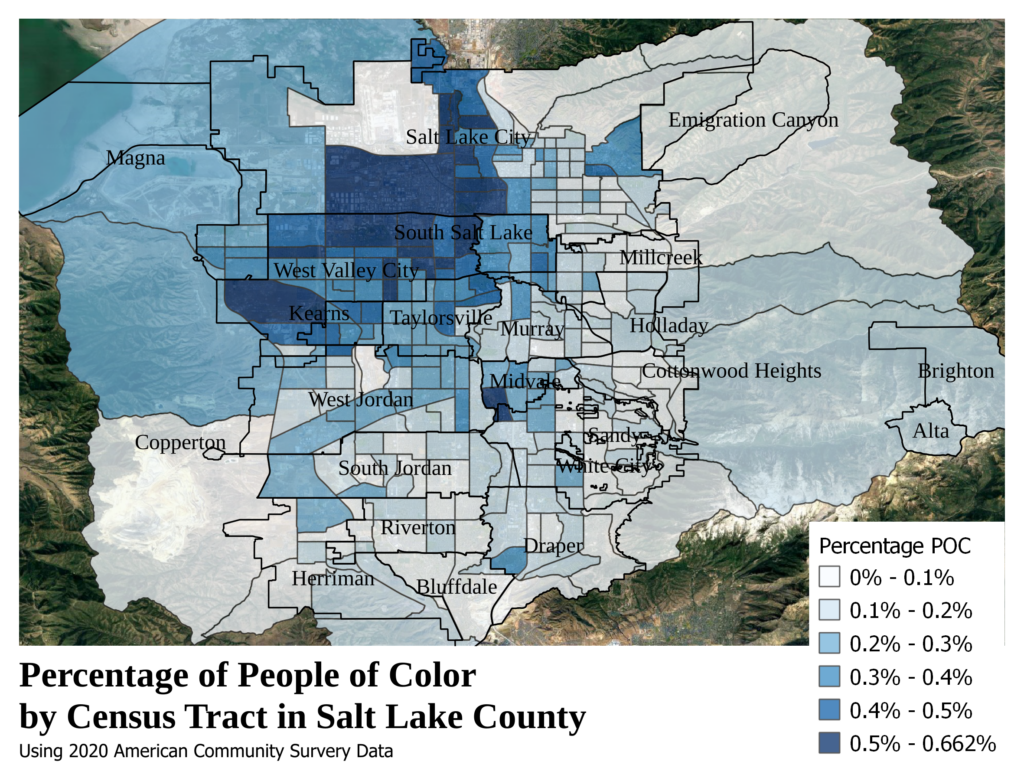

The history of city planning is the history of spatial segregation. It surprises no-one that there are upper and lower class areas in cities, affordability is often the privilege of pollution, disrepair, concentrated poverty, and disinvestment. In Salt Lake County, the divide is stark, following the topography of the valley. The upper class neighborhoods sit on the east side, resting below and creeping onto the Wasatch mountain range and flow south from there down to the border of Utah County, meanwhile the lower and working class neighborhoods sit in the center of the valley and sprawl out to the west side, crisscrossed by train tracks and highways, nestled beside the valleys industry and warehousing, and blanketed by smog and pollution.

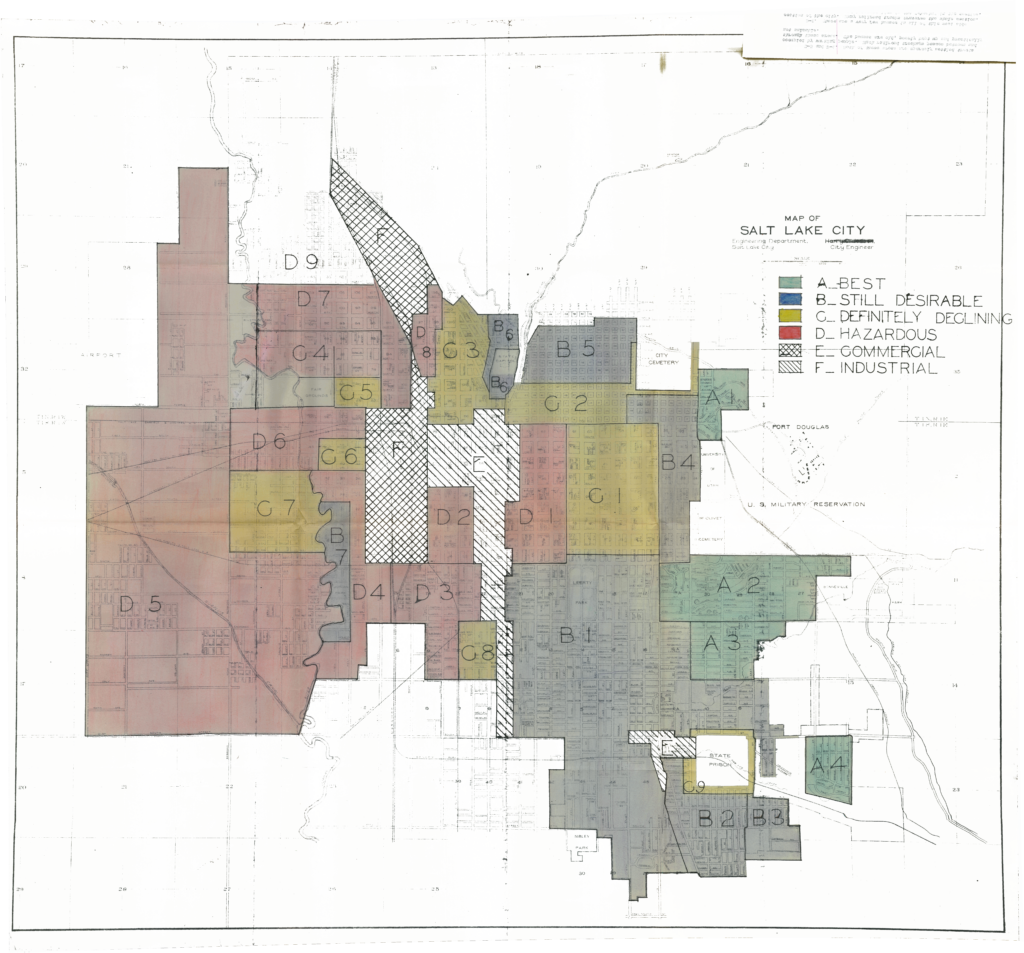

While the logic behind this segregation is complex and irreducible to any one factor, the historic roots of this racial and class distribution can be seen as early as the 1940s in the city’s Residential Security Map. Created by representatives of the local FIRE industries (Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate), alongside government officials, this map judged and divided the city based on “desirability”, solidifying the centers of concentrated capital1 in the Salt Lake Valley to this day.

This is the redlining map for Salt Lake City (“redlining” refers to the red-graded “Hazardous” sections of the city). It’s not hard to notice the similarities to how race and class are distributed across our valley today; the red and yellow graded neighborhoods sit in the center of the city and spread out covering nearly all the west side, while all the green graded neighborhoods are as far east as you could get. Except for the D1 neighborhood, all the redlined areas are separated from the blue and green graded areas by the commercial and industrial corridors, which cut the city in two. The segregation was deliberate and clear.

These maps were also notoriously racist, equating racial diversity to undesirability2, and despite having little diversity in the 1940s, the map for Salt Lake was no exception. In the description of the D1 neighborhood downtown, the map’s creators state they “found the only concentration of negros in the city”; this neighborhood was given the lowest grade.

Putting this map in its historic context, it’s important to understand that SLC in the 1940s was overwhelmingly white. With a total population of 149,934, SLC was 90.3% so-called “native-born” white, with another 8.9% being “foreign-born” white. This data, however, coming from the 1940 US Census, certainly turns a blind eye to the Latino population, who, for as long as the Census has been conducted, have been overlooked and long denied a unique formal identity. It might be that within the 8.9% of SLC that was “foreign-born” white lay the city’s Latino population, but it is also possible that the Latino population was counted in the 0.8% of the city that wasn’t coded as white. By the 1940s, the number of Latinos in SLC had decreased dramatically following a mass wave of repatriation and deportation in the 1930s in which “many of the state’s Latino/a population were forcibly removed and shipped to Mexico”3. These limits to using Census data reflect the white-supremacist attitude clear in every corner of the US. Even something as seemingly “objective” as the Census has been used to overlook, erase, and deny the existence of non-white people living in North America, an erasure which has worked to simultaneously hide and justify the genocide of the indigenous peoples who once called this valley, and this continent, home.

What we can say with more certainty is that this initial segregation was largely driven by class. In the description of every redlined area, reference is made to the “working people” and “laborers” who reside there. The message the maps creators were sending was clear, we may need a working class to work the service and industry jobs which keep us comfortable, but we’re going to put them as far away from us as we can.

Segregation is the tune to which cities have been planned the world over, and humanity is yet to create a city not tainted by the racism and exploitation of capitalism, but in deconstructing and understanding the foundations on which this place was and continues to be built may point the way to a future free of the dominations which plague our spaces today.

This is the first article of a new effort called Deconstructing Salt Lake aimed at making sense of this metropolis, from environmental injustice and ecological destruction to unsafe streets and gentrification, and just maybe also beginning to imagine what an authentic urbanism might look like in so-called Salt Lake.

– brick

1Capital is value in the capitalist system; it can be found in money and property and allows for the exploitative relationships between the holders of capital and those dispossessed of it, these relationships make and remake capitalism every day (boss-worker, bank-mortgage holder, landlord-renter, consumer-worker, etc.)

2https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/

3https://community.utah.gov/latino-as-and-the-west-side-part-two/

During the George Floyd uprising in the Summer of 2020, the marches through Salt Lake City would often stop on one of the Trax lines downtown with the “organizers” of the march claiming that by disrupting the Trax we were in fact putting a damper on the creation of money (that is value production) in Salt Lake; while the efficacy of attacking capital by sitting on light-rail tracks can and maybe should be questioned, I doubt the organizers speaking through their megaphones knew how right they really were.

During the George Floyd uprising in the Summer of 2020, the marches through Salt Lake City would often stop on one of the Trax lines downtown with the “organizers” of the march claiming that by disrupting the Trax we were in fact putting a damper on the creation of money (that is value production) in Salt Lake; while the efficacy of attacking capital by sitting on light-rail tracks can and maybe should be questioned, I doubt the organizers speaking through their megaphones knew how right they really were.