Salt Lake City (SLC), like many urban areas in the United States, is home to recurring land conflicts between the homeless and the city, county, state, and private landowners. As the city notes on their Homeless Services Dashboard, “…we as a City cannot sacrifice the safety of our neighborhoods when encampments become associated with crime and environmental degradation”[1]. In response to homeless encampments the city conducts regular abatements through the Salt Lake County Health Department (SLCHD). According to a SLC budget amendment filed on March 1, 2021, over 1,000 health department camp cleanups occurred in 2020[2]. Given their association with crime, encampment abatements are often accompanied by the Salt Lake City Police Department (SLCPD), with 30 to 40 officers and up to six sergeants required dependent on the size and location of a camp. According to the budget amendment these officers require an additional budgetary allotment of $650,000 for the 2020-2021 fiscal year.

Given the frequency and cost associated with ongoing abatements there is relatively little data regarding the placement or number of encampments throughout the city or the efficacy of abatements in limiting homelessness. Once a year the State of Utah presents an Annual Report on Homelessness. These reports include point-in-time counts (PIT), as mandated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The PIT conducted on January 28, 2021 for Salt Lake County found 623 unsheltered individuals, a dramatic increase of 355 individuals from 2020’s count of only 268[3]. This rise in homelessness was documented amidst changes in survey strategies due to the complications of the COVID-19 pandemic, making straight comparisons challenging. However, the sheer change in volume is worthy of further examination. In addition to these yearly reports the city hosts a map of cleanup services anonymously requested through the SLC Mobile Application which can be found here. These clean up calls are aggregated over three-month intervals. While more specific than the annual reports, and giving some geographic context, this map is not a flawless depiction of homeless encampments or individuals as calls for service are likely biased towards more heavily trafficked or affluent areas. The limitations of this type of encampment mapping are described in Corinth and Finley’s 2020 work which used “311” calls in New York City to produce similar results[4]. The temporally course nature of these data sets, and their lack of geographic specificity, makes it challenging to assess where encampments form, why and how they persist, or the effects of the city’s regular abatements.

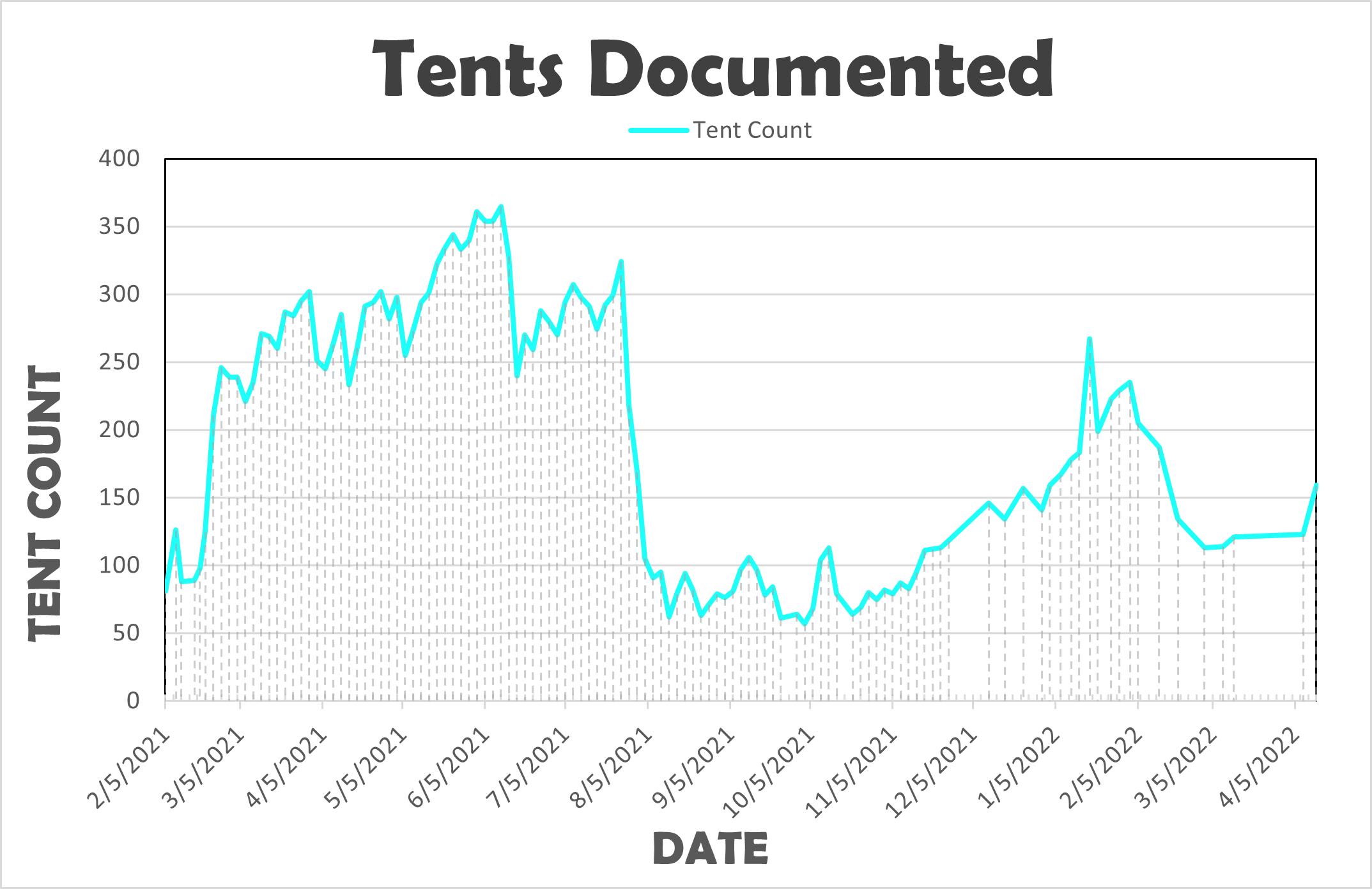

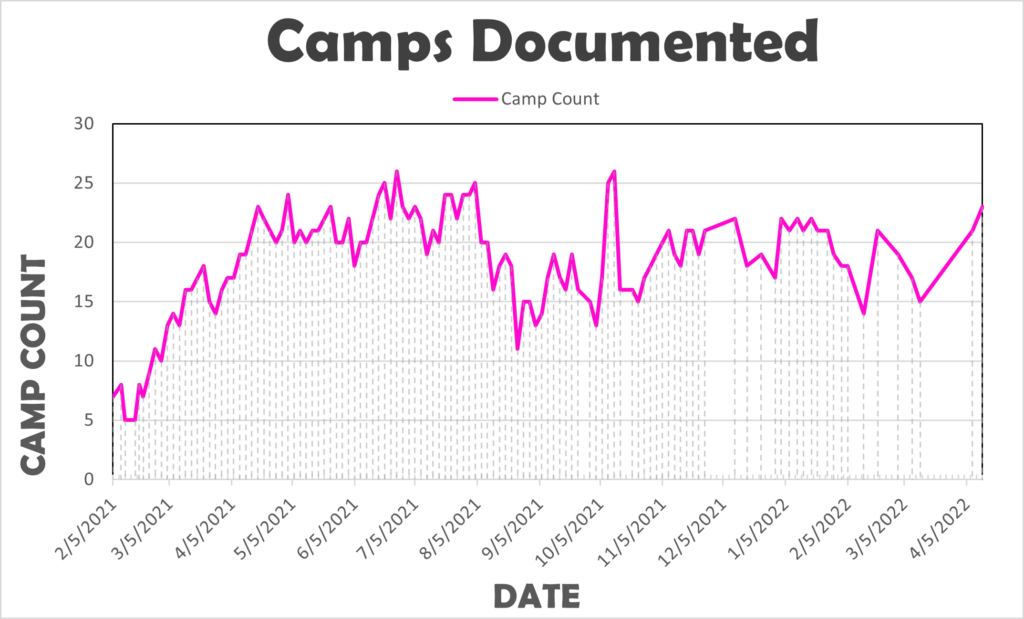

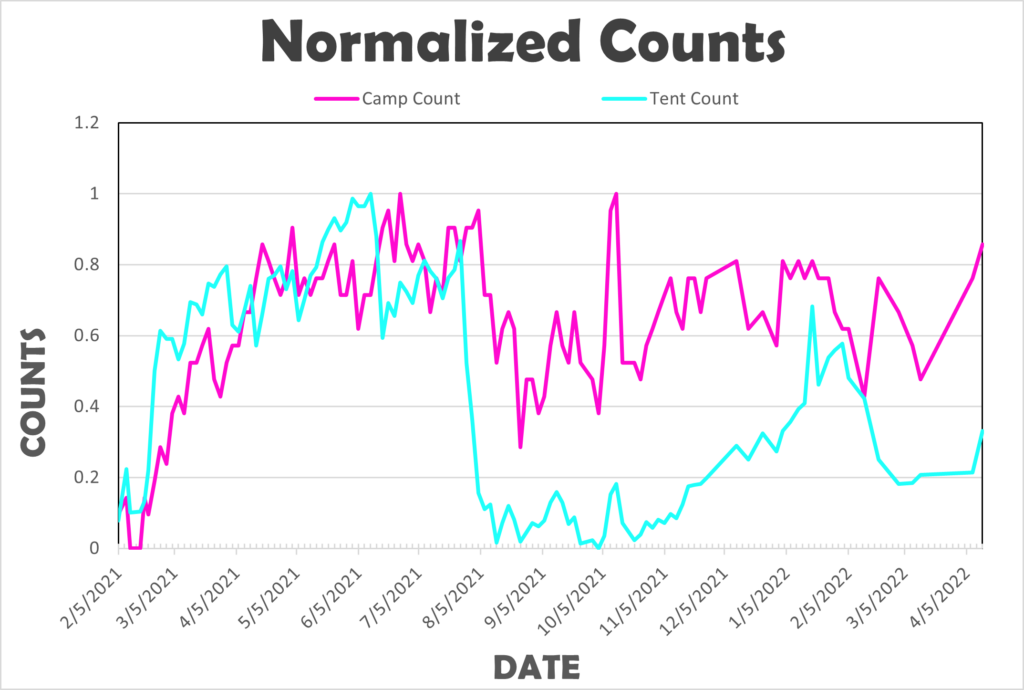

To address these limitations the Salt Lake City Homeless Encampments Dataset (SLCHED) was begun on February 5th, 2021 following the abatement of Camp Last Hope. Camp Last Hope was “the largest and most organized homeless encampment Salt Lake City [had] seen in recent years” according to the Salt Lake Tribune[5]. After Camp Last Hope’s dislocation many homeless were spread throughout the city in smaller encampments making outreach and support challenging. To address this the SLCHED records the size and geographic extent of homeless encampments throughout the city approximately every three days. This fine resolution database made it possible to keep up with encampments and ensure that resources were getting to all those displaced by the abatement. Initially begun to better assist with outreach efforts, this mapping dataset has since proven to be valuable in critically understanding the placement, growth, and adaptation of camps over time as the homeless community responds to abatements and changing weather conditions. Utilizing open-source GIS software and a PostGIS database, the SLCHED allows researchers and activists to critically examine the context and placement of camps beyond the limited data provided by the state. Some examples of the visualization and data provided by the SLCHED are given below.

[1] Homeless services dashboard. (2021, April). online. Retrieved from https://www.slc.gov/hand/homeless-services-dashboard/

[2] Thompson, M. B. (2021). Salt Lake City Department of Finance. Retrieved from https://www.slcdocs.com/council/agendas/AdministrativeTransmittal/2021/RevisedBudgetAmendmentNo7senttocouncil3_1_2021.pdf

[3] Workforce Services. (2021). State of Utah annual report on homelessness 2021. Housing & Community Development. Retrieved from https://jobs.utah.gov/homelessness/homelessnessreport.pdf

[4] Corinth, K., & Finley, G. (2020). The geography of unsheltered homelessness in the city: Evidence from “311” calls in new york. Journal of Regional Science, 60 (4), 628–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12478

[5] Stevens, T. (2021). Camp last hope in salt lake city dispersing ahead of planned health department sweep – many of the dozens of unsheltered individuals who have been living there will move to smaller encampments in the city. The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.sltrib.com/news/politics/2021/02/04/camp-last-hope-salt-lake/